There’s an exciting prediction sweeping through tech prognostications right now: the rise of the "one-person unicorn".

Sam Altman predicted that we’ll soon see a single individual build a billion-dollar business, noting that in his group chats, "there's this betting pool for the first year there is a one-person billion-dollar company." Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, has put his chips on 2026 as the year this happens.

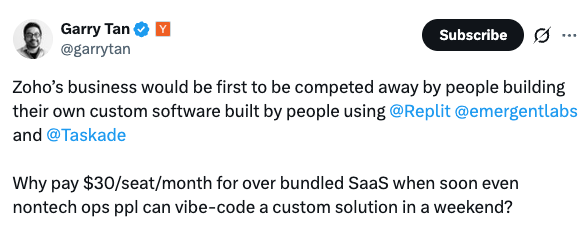

Gary Tan goes even further, predicting the death of SaaS: “Why pay for Salesforce or Zoho when a non-technical operator can "vibe-code a custom solution in a weekend?"

The consensus view is that AI is the ultimate decentralizing force, a tool that empowers the sovereign individual to out-compete the organization.

The premise, that AI dramatically reduces the cost of production, is correct. But the conclusion, that this leads to a highly fragmented world of creators and solopreneurs building their own tools and businesses, is likely wrong.

History suggests that when production becomes trivial, value does not disperse to the edges; it accrues to the entities that can master scale.

Consider the once-revolutionary, but now humble, sewing machine. When it was introduced in the 19th century, it was hailed as a miracle of individual empowerment. Suddenly, the time required to sew a shirt dropped from fourteen hours to one. The logical prediction at the time was that households would become self-sufficient, able to whip up whatever clothing they needed whenever they needed it.

But that isn’t what happened. The sewing machine did not lead to a world where everyone made their own clothes; it led to the "ready-to-wear" industry. It shifted advantage to the factories that could organize hundreds of sewing machines at scale, driving down costs and increasing reliability so dramatically that home-sewing became a hobby, not an economy. Yes, you could do it yourself, but why bother?

AI fits squarely into this pattern. It isn’t driving us toward a cottage industry of artisan innovators; it is driving us toward the era of innovation at scale.

AI coding attacks the cost of innovative creation itself, ushering in a phase of “first-version triviality.” It transforms software development from a labor-constrained process (how many engineers can I hire?) to a compute-constrained process (how much intelligence can I rent?).

When the cost of building something shifts this precipitously, the bottleneck moves. The hard problems are no longer about how to build the thing, but what to build, how to distribute it efficiently, and how to maintain and expand it.

This brings us to the "Death of SaaS" argument. If anyone can "vibe-code" a CRM in a weekend, why would anyone buy Salesforce again?

The answer lies in economies of scale. While one-off creation may be cheap for the individual, the alternative–mass production by an institution–is becoming cheaper and better at an even faster rate.

A solo operator can build a custom CRM on a Saturday. But by Tuesday, they need to patch a security vulnerability, and by Wednesday, they need to update the mobile view. The burden of maintenance is real.

But the true clincher is value capture through scale. When an institution adopts these AI tools, the cost reduction is applied across millions of units or users. The institution captures the same efficiency gains as the individual, but magnifies them through scale and focus.

Just as the factory-made shirt became cheaper to buy than the homemade shirt was to make, while offering similar levels of “custom fit,” the "ready-to-wear" software produced by the institution will win on price, reliability, and convenience.

This shift creates an opening for a new organizational structure: the Institutional Innovator.

Early versions of the Institutional Innovator can be found in today’s venture studios and mature startups. Anthropic itself recently exemplified the embodiment of the Institutional Innovator, leveraging Claude Code to build Claude Cowork in under two weeks. When asked how much of the code was written by Claude Code, Engineering Lead Boris Cherny confirmed: “All of it.”

The mature version of the Institutional Innovator will look like a modern factory, churning out numerous variants of an offering to meet the needs of its varied customer segments.

If the craftsman era of innovation was defined by unique teams solving unique problems, the Institutional Innovator is defined by a shared production line that generates similar but slightly varied solutions as its output. This entity will truly tap into the advantages of parallel entrepreneurship:

In the craftsman era, every startup built its own infrastructure, creating unique authentication, billing, compliance, and data architecture. The introduction of reusable components like Stripe for payments accelerated this process, but assembly remained slow.

In the AI era, the Institutional Innovator builds a shared, base solution and produces custom solutions—possibly even new companies—as variations on that base. This allows for the rapid production of vertical software, such as a CRM for roofers or an ERP for boutique clinics. These markets were previously too small to justify the fixed cost of a bespoke startup, but when they roll off a shared assembly line, the economics change entirely.

A serial entrepreneur learns sequentially: build one company, learn the hard lessons, start the next one five years later. The Institutional Innovator learns exponentially.

Because it runs parallel experiments, if a solution in the healthcare vertical hits friction, the solution in the logistics vertical learns from that friction and adapts in parallel. The system improves the process of company building, not just the product.

In the craft model, a founder bets everything on a single prototype. In this model, the Institutional Innovator manages risk like a manufacturer. Because the cost of prototyping is so low, it can spin up ten concepts, rapidly test them against market realities, and scrap seven—all before seeking external capital. It internalizes the "seed stage" of venture capital.

Crucially, this industrial model does not make the human founder or product manager obsolete. It liberates them.

For the last decade, the technical resource was the scarcest asset in the ecosystem. Innovators were forced to spend the majority of their resources building the solution instead of refining their understanding of what to build, optimizing it for various consumer segments, or streamlining distribution.

The Institutional Innovator inverts this. By commoditizing the manufacturing and distribution, it allows the product co-founder to spend their time where it actually matters: with the customer.

Sam Altman is likely right: we probably will see a one-person billion-dollar company in the near future, and we’re already seeing tinkerers opting to build their own tools.

But the bulk of the value of AI won’t be captured by that tinkerer hacking away in a garage. It will be captured by the Institutional Innovator, leveraging AI to fulfill their customers’ unique needs faster, cheaper, and more reliably than the customers and tinkerers could ever do themselves.